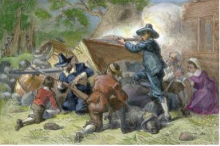

The Bacon Rebellion was largely a response to the inaction by the Jamestown elite in protecting homesteaders further to the west and under constant threat of Indian invasion. The city’s rich preferred a poor white buffer between themselves in the east and the unsettled lands in the west, populated as they were by hostile Indian tribes. However, that was not the only reason for the poor colonists to revolt. Farmers and ranchers in the area wrote often about merchants monopolizing much of the trade in the colonies, and being given special treatment if they were English.

The great discrepancy between the few wealthy families in control and the multitudes of poor in the colonies was largely due to two influences. Most poor were fleeing other nations that had begun to crack down heavily on the impoverished; whipping or mutilating beggers, making theft a capitol punishment, etc. The reason that these nations had instituted such a crackdown is the same as why imperialism became such a fad around the 17th and 18th centuries; they’d run out of room in their homelands but, because of the onset of the Industrial Age, desperately needed it. Major urban centers were overrun with displaced rural poor, and so they had only one solution; make being poor in the city so unbearable that they’ll cross an ocean to avoid it.

Though a common conception, and one we’ve wholeheartedly carried with us into the 21st century, is that these poor were able to work themselves into prosperity and wealth from the bottom classes. However, cited by Zinn are several sources that say that only very rarely did a man create wealth after arriving in the colonies. The vast majority of the wealthy had arrived with it, and had been put in a place of power to preserve and build upon that wealth; almost always on the backs of black slaves or indentured white servants pulled form the ranks colony’s poor. By 1700 the class division had become systemic, with several dozen wealthy families in control of the entire colony of Virginia.

In this lies the very misconception (one that is even perpetuated today) that the nation has always held a democratic essence in which all people, of lowest or highest means, are represented. However, in these early statehouses the governing bodies, though run democratically, were held year-to-year by an small group of merchant aristocrats made decisions “for the good of the colony” that ultimately benefited only one another. It is the same pageant that is played today, albeit on a much grander and more intricate scale, on Capitol Hill and on Wall Street.

It is a perpetuation of the idea that through the opaque lens of conservation of American values, the rich continue to get richer and the poor continue to get poorer; of a financial and political caste system that hides behind the twin towers of capitalism and democracy. I suppose that was Howard Zinn’s point in writing this book; so that we can learn about what America’s real values have been, and go about changing them to the values we’ve all been told about.