The Revolutionary War, according to Zinn, was an example of trading one tyranny for another (hence the title of the chapter). He points to the end of the French and Indian War (also called The Seven year’s War) in which the British had effectively eliminated French opposition in the New World, and would turn to the colonies to pay debts incurred by the conflict, as well as tightening control over the increasingly independent colonists.

There’s also the matter of the elite classes within the colonies worried about losing power and wealth to more British arrivals. Zinn writes that “the upper 5% of Boston’s taxpayers controlled 49% of the taxable assets in the city.” (60) Wealth was even more concentrated in New York and Philadelphia. The colonial elite that had before been able to sit back and watch their wealth pile up were now forced to watch it taken for war debt. The solution was to foment feelings of unrest, pooling the collective angst of the poor who had always been exploited, and the middle-class who were paying high taxes on commodities and trade taxes. The lion’s share of the wealth, however, was being paid by the wealthiest in the cities. Samuel Adams, one of the most famous, was also one of the first to incite rebellion, targeting those wealthy individuals that held Boston offices in the name of the English.

In one account a mob of of people lead by a local shoemaker ransacked the home of a wealthy British merchant, and then the home of a rich elite that ruled several colonies in the name of England. This was essentially the same popular anger and “wealth redistribution” that would take place in France during the Revolution, and similarly, it was incited by the wealthy that saw an incredible weapon in the discontent of the lower classes. As Zinn writes, “We have here the forecast of the long history of American politics, the mobilization of lower-class energy by upper-class politicians, for their own purposes. By directing the lower classes to vent their frustrations on British-supporting wealthy locals, they were protecting themselves and making it increasingly difficult for the British to tighten controls.

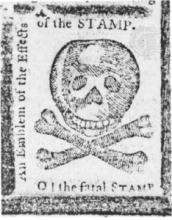

After the riots of the 1767 Stamp Act the privileged instigators were given pause. The mob that took to that streets of Boston that evening were insatiable as they ransacked one wealthy homestead after another, looting shops and even raiding the Lieutenant Governor’s mansion. The individuals inciting the fury became concerned that the riots may turn on their own homes, their own wealth. In response to these types of riots the British gradually began to deploy more troops to Boston; thousands that impressedpeople’s homes and businesses into quartering them. In 1770 impressment, continued taxation, abuses by British officials, and further instigation on the part of wealthy anti-British upper-classmen resulted in a march on the customhouse. British soldiers, intimidated by the mob, fired on them, killing seven. This was the Bostom Massacre and gave rise to even further anti-British sentiment.

By 1773 the Boston Committee of Correspondence had formed to organize anti-British actions and sentiment. The Boston Tea Party was one. The Sons of Liberty, a group of middle and upper-class colonials emphasized restraint in the destruction of private property, but not in the seizure or coercion of British officials. There still remained, however, the fact that the mods were made up of primarily lower and lower-middle-class individuals while the rich often incited them with fiery speeches, but did not take part. This didn’t go unnoticed, but it was Patrick Henry and Thomas Paine that closed the divide. They were widely published and spoke often about the need to unite to rise against the British. Paine was especially adept at stirring rebellion against the British with early nationalistic rhetoric, although he was also directly financed by one of the richest men in Pennsylvania, Robert Morris.

As the British took harsher steps toward retaliation and control, many of the upper-class revolutionaries understood that they would need to put some skin in the game. The result was the Declaration of Independence. It was the product of the meeting of this relatively small group of wealthy, well-connected men (formally convened as the Continental Congress) explicitly stating their intent to secede from British control that initiated the Revolutionary War, whether the common people that were not being incited to riot in the streets wanted it or not. It also created a new opportunity to build wealth; the seizure of all property belonging to the wealthy British officials and British-supporters in the colonies. It’s this motivation that may have been enough to sway those wealthy colonists that did not want to put stake in the war. Whatever the case, by 1776 everyone had to choose a side as the colonies descended into a full-scale revolution.