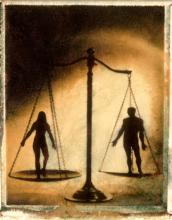

In Chapter 6 of A People's History, Howard Zinn devotes time to articulating the plight of the unacknowledged in history; that of women. In fact, he states that, "the very invisibility of women" in the annals of history is a sign of their submerged status.

In fact, Zinn points out one very important distinction between societies that seem to make women subservient in their roles as wife, child-bearer, and custodian to the home and offspring, and those societies that seem to place women in nearly equal standing to men in a more egalitarian family unit. That distinction is the concept of private property. "Societies based on private property and competition, in which monogamous families becom practical units for work and socialization, found it especially useful to establish this special status of women."(103) He points out that earlier societies, in the Americas and elsewhere, that held materials as common property, and in which extended families often lived in the same place, held a much more equitable role for women with men. They were essential in upholding traditions and customs in their teching of subsequent generations, and given special importance of stewards of large family units. The need to distinguish oneself within a power structure by material gain is a much more masculine mentality, and thus wasn't as important to these societies. It wasn't until white societies brough "civilization" and competition that it became necessary for women to be subjugated, even commodified by men according to their physical attributes and demeanors of "obedience" or "disobedience". Women essentially become a material commodity in the patriarchal societies of private possessions and competition.

As is the purpose of People's History, Zinn points out that the schoolbook history we're often taught is somewhat different from the truth. In bringing "civilization" to the New World, the Virginia colony also brought the first instance of the sex trade. The first settlers were primarily men, soldiers, merchants, and laborers that came to settle and build a colony. In 1619, the first year black slaves came to the colony, a ship from England arrived in Jamestown with 90 women. These women, the vast majority of which were teenaged girls, were brought as indentured servants to be the child-bearers, sex slaves, housekeepers, and general companions to the men of the colonies. Described as "agreeable persons, young and incorrupt" (i.e. virgins), these young girls were paid for by male colonists for the fee of transportation. They would serve a term of "service" to their owners, after which period they would again be free to pursue a life of their own. They were expected to be obedient to their masters and mistresses, and Zinn writes of a number of situations in which colonial courts beat, incarcerated, or publicaly humiliated those that weren't.

If white women were objectified in such a way, black slave women were moreso, often giving birth aboard slave ships shackled to corpses that had not survived the journey across the Atlantic. As girls came of age masters were free to rape and beat them wih impunity, and such treatment was actually considered necessary by many white slaveowners so as to break their spirit and make them more obedient.

Even free white women, not brought for indentured servitude, faced special challenges. The earliest women settlers were often treated with respect because they were so sorely needed, and enjoyed some equality. But as survival became more certain, and more women arrived in the young colonies, ideas held over from England and the Christian teachings again relegated them to a role of subservience. Zinn relates the writings of one woman about her rights in the colonies, saying, "The husband's control over teh wife';s person extended to chastisement...but he was not allowed to give her permanent injury or death."(106) In fact, there are many examples of women that gave birth out of wedlock, a crime called "bastardy", in which mothers were severely punished while fathers were untouched by the law.

Puritan New England was of particular guilt in the subjugation of women int eh early colonies. A well-known Boston minister, Reverand Joseph Cotton, demanded wives, "be subject to your husbands in all things." It was in Massachusettes that Anne Hutchinson, an eloquent and intelligent woman that spoke against church and government concerning their treatment of women, was one of the first activists for women's rights in the New World. She held meetings and gathered popular support within her circles of influence. She was put on trial by the church for heresy, saying that people were capable of interpreting the Bible for themselves. She was also put on trial by the Massachusettes Bay Colonial government for sedition. When she was expelled from the colony in 1638 to Rhode Island, 38 families followed her. Indians there that had been defrauded of their land rights by the local government thought they were enemies and slaughtered them all. The only woman that had spoken up for Hutchinson in Massachusettes was hanged for sedition.

The legends of particular women, however, were somewhat elevated by the colonies entry into the Revolutionary War. Abigal Adams, Martha Washington, and Dolly Madison were wealthy and aristocratic women that wielded some influence in the political arena and have been heavily caricatured by historians. More interesting, however, are women like Margaret Corbin, Deborah Garnet, and "Molly Pritcher" were lower-class, rough-hewn women that many historians have recharacterized as prettified ladies. These revolutionary characters in women's liberation served to open the way for further movement in women's rights and equality. Thomas Paine, one of the great intellectual and rhetorical instigators of the Revolutionary War argued for women's equality. Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Caty Stanton, some years later, were two of the best known activists for women's sufferage and equality. There was still some way to go, however, in fighting Puritanical and ingrained social prejudice against women in 19th and 20th centuries.

It was in 1851 that an aged black woman that had been born a slave stood up against a handful of white ministers and told them, "Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted and gathered into barns and no man could head me! Ain't I a woman? I would work as much and eat as much as a man, when I could get it, and bear the lash as well! Ain't I a woman?"(124) This was Sojourner Truth, and is popularly believed to be the beginning of a very public campaign for women's sufferage in America, one that wouldn't be granted for another 75 years, and almost 200 years after those first young girls were sold as indentured slaves to white male settlers.